Pilates is highly regarded as a way of clinically keeping the body healthy, reducing injury, and rehabilitating from injury too. The evidence supporting the use of Pilates in these ways is profound and covers a huge range of conditions from back and neck pain, to pregnancy and postnatal, and even within sports. Not only does Pilates have a significant physical benefit to the body, but it also imposes a mental relief too through the powerful mind-body movement connection. Here we explain the theory behind Pilates!

But first, a quick summary of research showing the effects of Pilates exercises:

- Pilates exercises have been shown to be more effective long-term in treating first episodes of low back pain than medical management or normal activity alone (Hides et al. 2001).

- Treatment of low back pain with Pilates was more effective than the usual back care treatments in those with chronic, unresolved low back pain (Rydeard et al. 2006).

- Pilates in conjunction with physiotherapy is more effective in reducing pelvic pain than physiotherapy alone (Stuge et al. 2004).

- Pilates exercises are effective in reducing pain and disability in short and long term neck pain and headaches (Jul et al. 2002).

- A 6-week Pilates course significantly improves functional movement in recreational runners, and may lead to a reduction in injuries (Laws et al. 2017).

What is Pilates?

Pilates is an exercise form that emphasises the importance of beginning movement from a central core. From this core, the intensity of the exercise is adjusted by moving the arms/legs (to alter lever lengths) and by adding resistance (using Pilates equipment). When this is combined with appropriate breathing patterns the essence of the mind-body technique is evident.

Why does the core matter?

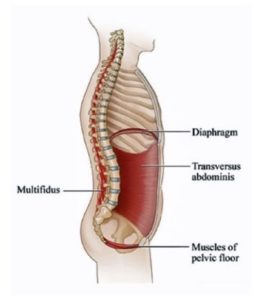

The core is made up of the transverses abdominis, the pelvic floor muscles, multifidus muscle, and the diaphragm. When these muscles are activated or contracted they have a collective response upon each other ie the activation of one will activate the others and produce a corset of support around the spine and trunk. Because the spine is made up of numerous small bones (the vertebrae) this muscle activation stabilises the spine, providing support and strength throughout. Increased core stability allows the spine to move through these vertebral segments without injury. If core stability is deficient, movements such as bending or reaching out away from the body can place extra strain on the vertebrae and cause damage and/or pain.

Research has proven that the transverses abdominis muscle has a separate cortical control centre in the brain from other muscles. This means that the transverses abdominis muscle becomes active BEFORE you actually carry out a movement! So before you move to bend over, or reach your arm out, the transverses abdominis will already be activated, protecting and supporting your trunk!

What happens when you have pain?

When you have pain present however (any amount of pain, but the effects are relative to the extent of pain), this pre-activation of your core is NOT present. In fact, the core muscles deplete with as much as 20% activation within 24 hours of pain. This causes a delay in the muscle activation, AND a reduction in the overall muscle strength, meaning you have less stability and support from the core, and are more likely to place strain on the other structures such as joints and ligaments.

Re-training of the core muscles has also been shown to cause changes within the brain at the motor cortex- the area of your brain that controls movement, posture control and body image. When you experience low back pain (or any aspect of pain) for example, the brain undergoes reorganisation of the motor cortex as the body adopts a deficient postural position that the brain perceives as “normal”. These alterations mean that the person has a lack of control over their trunk muscles and movements and an abnormal perception of their body posture and spatial awareness. Training the core has also been found to have a greater effect on influencing the brain’s reorganisation than strength training alone!

Therefore, learning to engage your core correctly and train it to be stronger is SO important for deeper spinal support, trunk stability, and supporting your overall body through movement.

The Instability Model (The Panjabi Model)

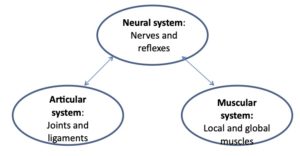

The model that is used to describe how stability is achieved in the body is called the Instability Model. This model shows how the joints, muscles and nerves within the body all coordinate together to provide stabilisation and control your spine’s movement. ANY disruption to this model ie through injury to one system will impair its overall function.

The muscles provide support through their active contraction and provide force closure (tightness) to the joints whilst the nerves control the signals to the muscles to function correctly. Force closure is the extra force produced by ligaments, muscles and fascia that compress joints to keep them tight together when load is increased, for example when walking or running. When there is reduced force closure we end up with instability, laxity, and potentially pain as the structures have too much movement and lack the support required.

“So this highlights why we need core strength and stability for normal body function and movement. The core provides the muscular system to support the articular (bones) and neural systems (nerves) and ensure total system efficiency”.

Next week we will discuss how Pilates actually came about, the importance of a correct breathing pattern, why positioning for exercises REALLY matters, and WHY there is a specific sequence to follow to do it correctly! All backed by the science! See you back here on the 22nd for Part 2!